Reframing: A Part of Social Change

Homelessness and A Memorable Screening at the King Center

One of the most compelling insights I’ve encountered about the power of reframing is from George Lakoff’s book, “Don’t Think of An Elephant.” He posits that reframing has the potential to create the kind of social change we desire, as it guides us to perceive things as they truly are.

Over the past few months, I’ve had the unique chance to screen my recent documentary, “Homesick,” across the nation. The film challenges audiences to think about how people frame and target the unhoused community with political rhetoric and criminality instead of addressing the issue in all its complexities.

And the film also indirectly asks people to consider how this impacts the community’s self-worth and belonging—when legislation often makes their existence in public spaces more challenging.

In my scholarly opinion, people in the social and political space need to change how they talk about homelessness—which ultimately creates the frames in which people see this population and how it informs how people treat it too.

Right now, the language used can be hurtful and often continues a cycle of opposing views and treatment of those who are unhoused.

According to Lakoff (2014), changing how we talk about things (or 'reframing') can help make social changes happen. Lakoff said that we can tell a better story using the right words, or 'frame'’ He explained that “framing is about finding language that matches your beliefs. It's not just about the words. The important part is the ideas, and the words are there to express those ideas.”1

The reactions have been universal—shock, awe, and deep sadness. People are invariably moved by the unhoused community's resiliency and ability to advocate against these policies themselves.

Then come the inevitable questions, “How do you deal with people who abuse drugs, those who refuse to work, the law-breakers, the ones making poor choices?” These questions often originate from a perspective tinged with suspicion, even fear.

I strive to give answers grounded in scholarship and affirm the dignity and humanity of each person, whether they have an address or not.

This primarily revolves around reshaping our discourse about people, influencing how we perceive, treat, and legislate for individuals, particularly those unhoused and impoverished.

I remember one screening vividly—The King Center’s “Be Love Day.” It held special significance because, while making the film, I relied heavily on Martin Luther King Jr.’s philosophy of the Beloved Community, an idea he expanded upon from Josiah Royce. Although King borrowed language from Royce, King’s approach to the Beloved Community was different:

Royce’s Beloved Community was primarily focused on a spiritual community. At the same time, King’s Beloved Community was more focused on creating a just and equitable society born out of his faith.

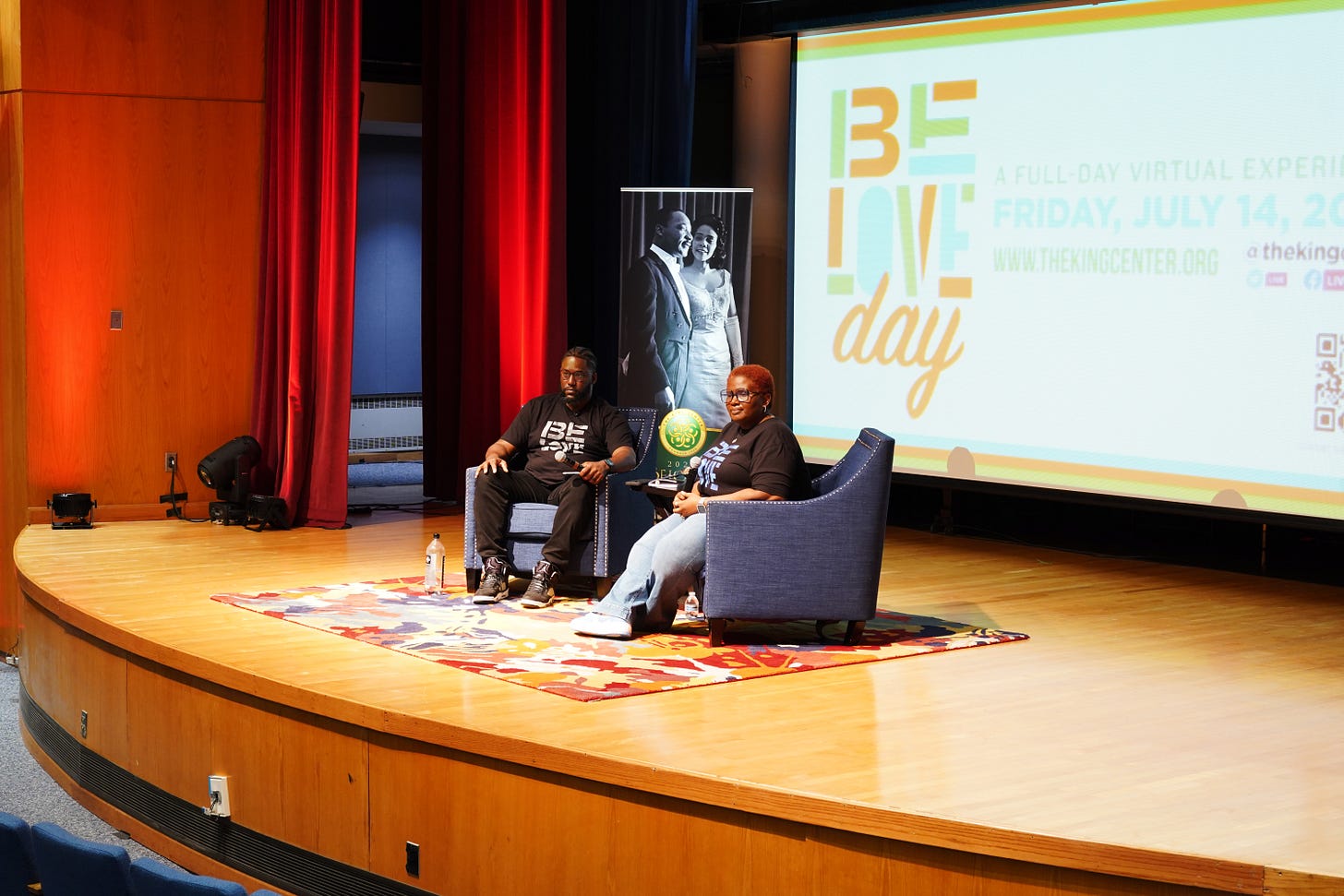

Following the screening, I had a panel discussion with my colleague and friend, Dr. Vonnetta West. One question she posed has stayed with me: why do I refer to people without a residence as the “unhoused” or “those experiencing homelessness,” never “homeless people.”

My answer was simple: “Homelessness is one of the few issues where we label people for what they lack, then penalize them for trying to survive that absence…” Our choice of words matters. They shape perceptions, influencing how we see those struggling with homelessness as part of the Beloved Community.

Reframing is crucial. It allows us to prioritize a person’s humanity over their difficulties. It involves adopting a language that offers a more empathetic, accurate representation of people, preventing stigma, stereotypes, and language from dehumanizing or marginalizing this cherished group.

Martin Luther King Jr. imagined the Beloved Community as a society rooted in love, justice, and equality, where everyone is accorded dignity and respect. In this spirit, using inclusive language and reframing our discussions about the unhoused community can:

Humanize the Unhoused: Reframing language shifts the narrative from defining people solely by their housing status to recognizing their deservingness of empathy and understanding.

Challenge Stigma: Using Beloved Community language can debunk the negative stereotypes and stigma frequently linked with homelessness. Reframing ensures we avoid reinforcing harmful assumptions and seeks to understand that homelessness is not a singular experience.

Encourage Empathy: Language that underscores our shared humanity nurtures empathy and compassion. This empathy can lead to a greater willingness to address the root causes of homelessness and work towards solutions—especially our perceptions.

Builds Solidarity and Advocacy: Reframing how we talk about people and issues can inform the need for advocacy for the unhoused and help diminish societal barriers. It reveals our interconnectedness which connects with Martin Luther King Jr.’s vision of the Beloved Community, marked by love and mutual concern.

Reframing our language surrounding homelessness and the unhoused, we move closer to realizing Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream of a Beloved Community where all people are treated with dignity, justice, and understanding.

If you want to explore homelessness in the U.S., please consider checking out the book“I See You: How Love Opens Our Eyes to Invisible People.”

Explore my book “When We Stand: The Power of Seeking Justice Together” to delve into the profound impact of community involvement and collective action for social change.

Discover “All God’s Children: How Confronting Buried History Can Build Racial Solidarity” to gain insight into the significance of understanding the historical narratives that shape individuals and foster racial solidarity.

Or, subscribe to the Love Beyond Walls Newsletter—visit the site and sign up.

Lakoff, G. (2014). Don’t think of an elephant!: Know your values and frame the debate. Chelsea Green Publishing, pg. 4.